The Dark Side of Curiosity: When Too Many Questions Become a Problem

It’s 4pm on a Thursday afternoon. Your submission for this month’s Board papers is due at 4:30pm. All week, you’ve been grappling with how to articulate the problem to describe what you believe to be the biggest challenge to your organisation’s growth plan. You’ve gone deep into the data, spoken with your colleagues, and thought long and hard, but it still doesn’t feel right. You’ve asked your boss for 10 minutes to see if you can crack the nut in time for the deadline.

The conversation starts naturally enough. A few questions to help align on the process so far. Just when you start to feel like you’ve given them enough information to be able to advise you, the next round of questions starts coming at you. ‘What if...’ that opened things up further when all you wanted to do was narrow them down.

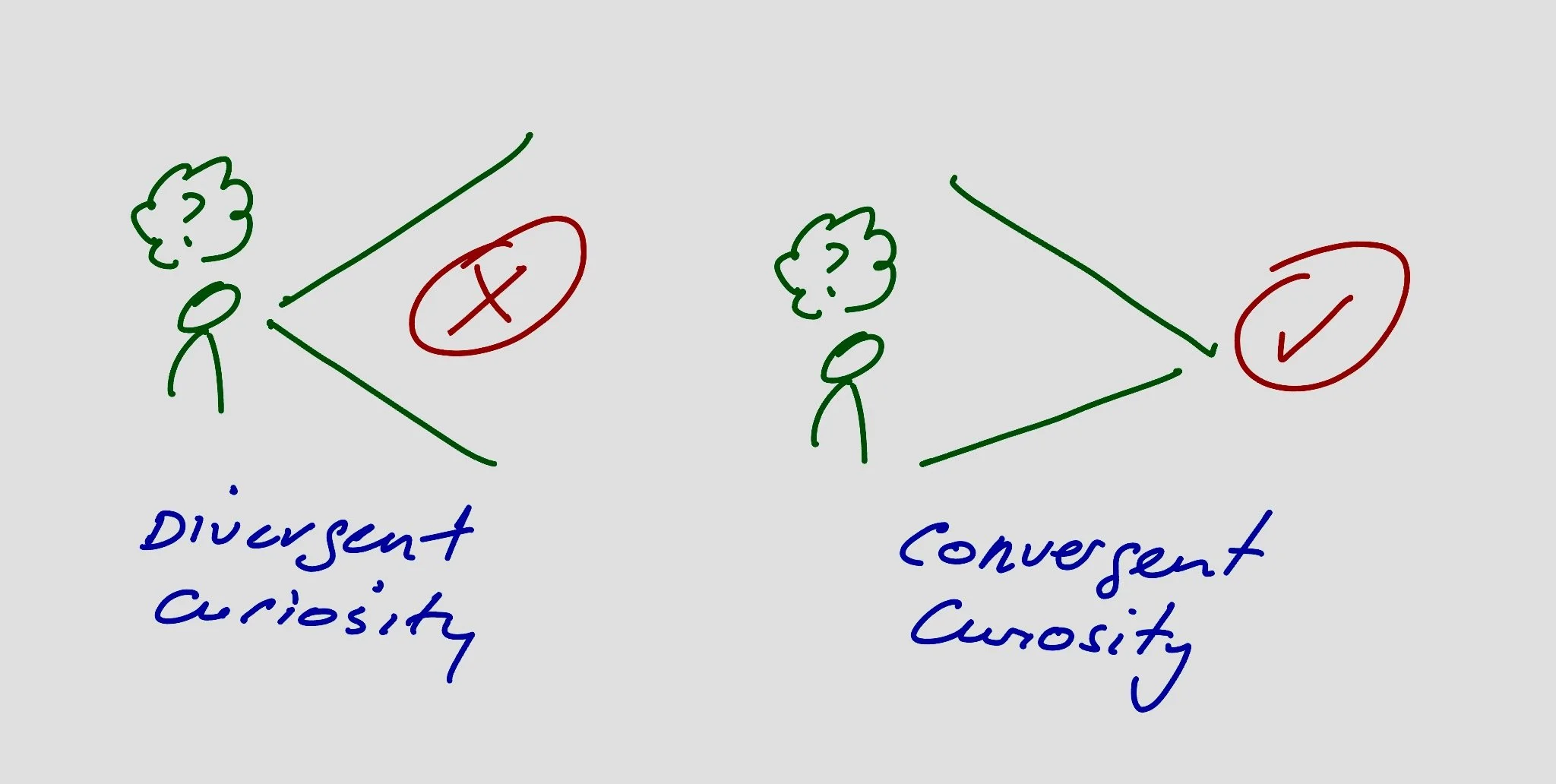

Your thoughts race between ‘hurry up, we’re on a deadline’ and ‘stop asking me questions and for the love of Pete, tell me what you think!’. Your frustration escalates while your ability to concentrate dissipates. Your boss’ divergent curiosity is incredibly valuable when you’re developing new ideas, but that’s not what you need from this conversation. You need convergent curiosity.

This scenario is a classic example of the ‘coaching trap’, where leaders who have invested time and energy developing their coaching capability only respond with questions, leaving their team members craving guidance and clarity. It’s confusing and erodes trust.

Curiosity is powerful and easily overused.

Questions are one of the most powerful tools in our leadership toolkit, but as highlighted by Abraham Maslow in 1966, when all you’ve got is a hammer, everything looks like a nail.

The ‘coaching trap’ isn’t the only pitfall to be aware of.

The ‘research rabbit hole’ shows up when leaders fear making the wrong decision, so they make no decision at all. They mask their fear by using questions as a delay tactic. Seemingly endless questions asked with no clear purpose risk leaving team members more confused and wondering why they bothered to consult in the first place. You’ll recognise the research rabbit hole when the response to a very direct, pointed question is...yes, you guessed it, another question.

The ‘grand inquisition’ tends to bombard our team members with questions, often while we try to show interest and engagement or attempt to demonstrate our intelligence. This can feel like too many questions, inappropriate questions, or both, often masking our own discomfort. A common example of the grand inquisition is a question (or three) that feels overly personal, intrusive, or asked at the wrong time.

The ‘hamster wheel’ is an endless cycle of exploring and choosing, as we pursue a (false) sense of control over a situation. Often referred to as ‘analysis paralysis, this can look a lot like the coaching trap, and based on my observations of coaching leadership teams, they often co-exist. If you’ve ever presented a series of recommendations only to be asked, ‘but what about...?’ (after multiple revisions), then you’re probably experiencing the hamster wheel.

It’s easier to see these traps in others, but how can we recognise them in ourselves?

Watch the body language of others. Do they seem engaged in our conversation, or have they lost focus? Nodding, eye contact, and leaning forward are all positive signs to look for.

Keep a list of the decisions that feel most important or risky. When attending meetings on those topics, take an extra 5 minutes before showing up to set your intentions and ‘turn on’ your self-awareness.

Limit your initial personal questions to one or two. Once you’ve received open responses (and been asked some in return), you’ll be in a better position to judge whether it’s OK to keep going.

While the traps are easy to fall into, there are some simple ways to avoid them, or at least minimise their impact.

Tips for maintaining the power of your curiosity

If you recognise yourself in any of the scenarios I’ve described, here are some tips to help maintain the power of your questions.

Recognise your context - take a moment to identify what is most needed from you in that moment. Is your team member asking you to help them think bigger, or do they need you to make a decision?

Acknowledge your vulnerabilities - reflect on situations where you might be likely to overuse curiosity. Share those insights with your team so they can highlight them if it does occur.

Declare your intentions - Clarify your understanding of the purpose of the conversation. Calibrate this with your team and explain how you plan to help them.

Design your questions - carefully consider both the type and amount of questions that will achieve the purpose. If you’re looking for some question inspiration, check out my book, Curious Leadership: 50 Powerful Questions for Leaders at Every Level. You’ll find it here.

Ask with care - ask your questions with thoughtful consideration for tone and pace.

Check in - seek feedback at the end to ensure your actions are aligned with the purpose of the conversation (and integrate any learnings next time)

Back to that Thursday afternoon conversation. Imagine if your boss had started by asking, "It sounds like we need to quickly narrow the issue to meet the deadline. What is the question you want me to answer?" Same curiosity, but now it's precise and aligned with the urgent need.

This is the real power of curiosity in leadership: asking the right questions at the right time. When we are curious with intent, we avoid the traps, build trust, and accelerate decision-making.

The next time you’re about to ask a question, pause and consider: "What does this person need from me right now?" Your curiosity will become more powerful and more purposeful too.

I coach leaders and their teams to ask and answer the powerful questions that drive results. Let's schedule a conversation today!